Our Logo Story

On a Spring Saturday on the Old Course in 1914, the wind was from the north out of the Perthshire hills, and it was the club finals for the annual golf trophy of the Royal & Ancient Golf Club founded 260 years earlier in 1754.

In the championship match, the two competitors were Major Charles Foxworth whose family home and estate were just south near the seaside town of Crail, and General Harold Danes who resided near the Aldershot Barracks in Surrey. Danes was a career army officer having risen through the ranks with success in military maneuvers, and with the assistance of his father who as a member of Sunningdale Golf Club hosted and entertained much of the then British general staff.

Major Charles was the only son of Lord and Lady Foxworth. In his early years, his father and mother had him work with the staff at the estate cleaning stables and shearing sheep. Their one guiding advice to their son was “to respect your fellow man and woman and to always try your best”. After finishing school at the University of St. Andrews, Charles joined the British Army. He had earned his rank of Major owing to service as a sub-lieutenant in the Boer War in 1901 where he was awarded a DSO. He was also a member of the 51st Highland Division of the British Army.

The supporting cast was two young caddies. One was born locally, and the other had come from a military barracks south from London.

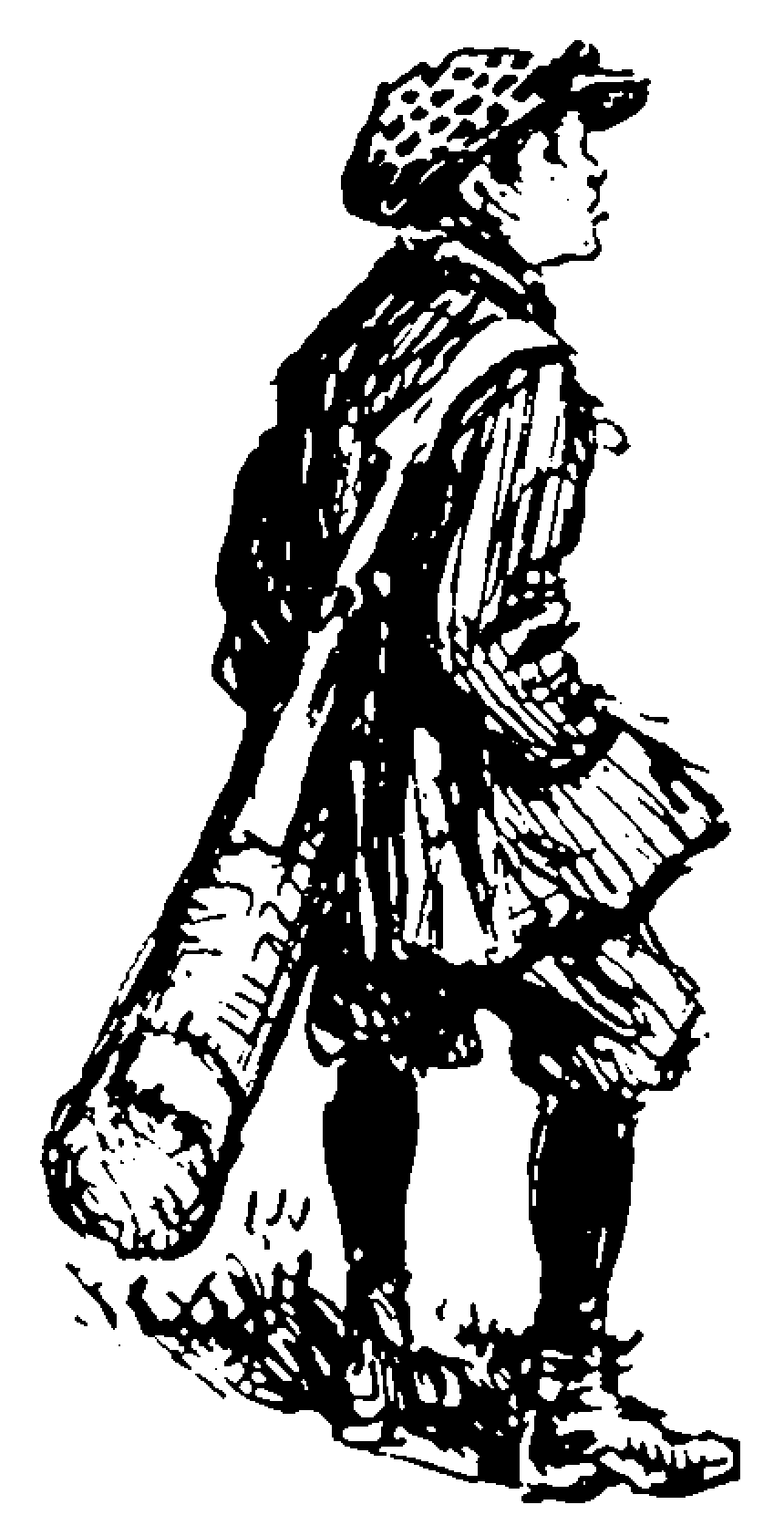

Oliver Morris, aged 12, lived with his widowed mother Mary in a small cottage near Anstruther. His father taught him golf on the links at Crail, and when his son was caddying for him, explained the integrity of the game of golf whereby the competitors were solely responsible for playing by the rules of the game. In those days there were no officials walking with the golfers. One Sunday while Oliver was ill, his father left for a fresh catch, and had died during a fierce storm on the North Sea when his boat capsized and sank.

After his death, Oliver left school to help his mother keep their cottage and home from foreclosure – doing this with his caddy work on the links at St. Andrews, and by spending evenings in a local shop near his home, planning barrel staves for the whiskey distillery just outside of Edinburgh.

It was in early of the spring of 1914 with some surprise he saw Oliver, waiting with the other caddies to carry clubs for the elite members of the R & A. He asked the boy over, and questioned why he was not working at the shop or at home with his mother. The answer froze the Major, and he knew at once the boy would be his caddy. For Charles had lost his son and wife at childbirth in 1911, and their family losses were now a common bond.

The other caddy was a 17-year old corporal from Aldershot – David MacMillan – ordered to St. Andrews by the General to be his personal valet and to carry his clubs during the match.

Play had been close, keen and intense. But young Morris had, as always, handed from his small canvas golf bag, the proper club, and on each green, given the correct putting line. And the Major was in command of the match, relying on the skill of his little friend.

The competition came down to the difficult par 4, 17th hole, and the Major, leading by one, was on the green in two as was the General. A large crowd from the town and University had gathered around the 17th green, and was comprised of friends of the Major, students who cared much for the work of his mother (and naturally knew her son was part of the match) and officials and members of the R & A. While both competitors carefully studied the green contours and direction in which the grass had grown as well as the wind conditions, Oliver walked a circle around the stationary golf balls to determine his choice for the Major. With no warning the booming voice of the General declared, “the lad has stepped on my putting line and caused my ball to move, and I demand victory and the club trophy”. To which the Major replied – “nonsense, the boy has kept clear of all putting lines: ask those who are watching this match”; a great hoot along with boos went up from the surrounding crowd as well as cries of “play on coward”. The now red-faced General returned to address his ball, for the townsfolk and members of the R & A had spoken and ruled against him. The putt was badly missed, while the Major calmly holed from 20 feet and had his victory. He turned to Oliver, and said “once again lad you have brought me safely home and given me the courage to win”. He then went to shake the General’s hand as courtesy required, and to make peace, but his opponent had stormed off the green and headed to his first class carriage on the train at St. Andrews Station, which was making steam for the London run.

The Great War fell on Britain in August 1914, and the Major went to the front where he fought and was wounded on the Somme and at Arras. In early 1918 he was resting behind the town of Albert in France, not fully recovered from his wounds, but in charge of what was to become a key battalion – later attributed by historians – in stopping the onslaught of the Germans’ Ludendorff Offensive.

Oliver had spent the early war years, instead of making barrels, building coffins for the fallen British who had died during the retreat at Mons in Belgium, and at the disastrous frontal assault on the Somme. The Old Course had closed for the duration of the war and the University had very few students. So income was a problem for Mary and her son. They moved south to London, informing the Foxworth family of their plans. They continued to keep in touch with the Major through the Foxworth family, and knew he was resting in reserve behind the front lines near the trenches behind Albert.

But it was in early March 1918 that Oliver spied the newspaper headline of the great German breakthrough on the Somme and attacks towards Albert. There was but one thought and that was to go to the side of his friend and mentor – the Major. He spoke about this with passion to his mother, and she knew which course he should take. Though only 16 and wearing a borrowed uniform, which his aunt had just repaired from the bullet holes from the latest battle, he clung to his mother and aunt and bade them farewell. The 51st Highland Division patch had been sewn on the shoulder of the borrowed tunic by his mother – for Lady Foxworth had sent this to her along with news of her son. Underneath Mary had stitched “God speed my son” .

He then boarded the train to Dover and then the ship to France. Among the many thousands of British soldiers being sent to the front to fill the breach made by the force of the surprise German attack, he appeared to be a natural part of the reinforcements. The only comment that he overheard during this fateful journey to France was “they are certainly sending them bloody young these days”. The trip from Dover by ship embarked the troops near Etaples in France. This was the staging point for organizing the reinforcements to save the British Army. A sergeant with three wound stripes on his sleeve, sorted the troops, and at once saw the 51st Highland patch for he had served with the Major on the Somme. He ordered the boy to board the last train to Albert. The German artillery had wrecked the rail lines some 4 miles from the depot at Albert so Oliver left the train and made his way forward with the stragglers and troops trying to regroup and repel the German attack. As they approached the shattered British line, he began his inquiries for the 51st Highland Division in his final search for his friend.

The German massive advance across Flanders finally reached an end on April 4, 1918 at Amiens. As the counter attacking British troops moved forward to recover the lost ground they came upon a shallow trench with a broken machine gun; they also saw the body of a Scottish officer, surrounded by the 14 Germans that had died while he held his position. Next to him holding an ammunition belt lay a young boy, and oddly enough on his back was a canvas bag with three golf clubs and a rifle inside.

At the common war cemetery (rebuilt from the early crude graves of 1918, and at the commission of the British Government) just outside Albert, at plot 14 there are two adjacent headstones – often covered with flowers. The inscriptions read “Major Charles Foxworth – Victoria Cross” and the other, “a hero of the war – unknown except to God”.